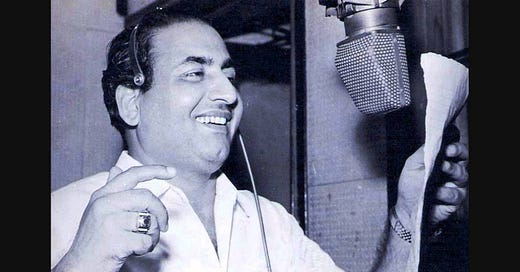

The house I grew up in, I lived with my Aai, Baba, brother, lovingly called Golu, Aaji, Azoba, and Mohammed Rafi. In 1997, when Compact Discs or CDs were becoming all the rage, Baba bought a three-in-one music system. It could play cassettes, CDs, and the radio. That year, for their wedding anniversary, Baba got a 12-cassette collection of Mohammed Rafi songs for Aai. All of Rafi's moods put together in one large box. Rafi then became a permanent member of our household. He would join us for dinners and sometimes would wake the tiny residents of the house in the wee hours of the morning.

But before I knew his voice, before the music system, even before the television, Rafi came to me in the voice of my Baba. Every Sunday morning, which would be the only day when I was allowed to sleep in late, Baba would come to my bed, and start singing, loudly might I add, Pukarta, chala hun main, gali gali bahar ki (I am calling out, I am walking through every street where spring has visited). I would wake up, crib about his voice ruining my sleep, and he would say it wasn’t him; it was Mohammed Rafi. And Rafi’s voice can’t ruin anything.

Baba’s voice had Rafi’s softness, even if not his melody and understanding of the surs and the taals. But Rafi could be Baba’s voice, and Baba could be the face of Rafi’s voice. That’s the thing about my housemate, Mohammed Rafi.

A simple Google search, for instance, would let you know that in a career spanning 40 years, the man has sung over 26,000 songs in various languages, including Hindi, Punjabi, and others. In this, while he has constantly been the voice of Shammi Kapoor, a whopping 190 times, the second highest has been for Johnny Walker. Rafi sang a little north of 140 songs for Johnny Walker. But it would be a disservice to Rafi and his musical brilliance to reduce him to mere statistics.

When I began working on this essay, the first thing I did was to start looking up the work that has already been done on him. I found a few books, all biographies, one by his daughter-in-law, Yasmin Khalid Rafi — Mohammed Rafi My Abba. The other by Sujata Dev — Mohammed Rafi, Golden Voice of the Silver Screen and another by Raju Korti and Dhirendra Jain — Mohammed Rafi, God’s Own Voice.

Then there was a slew of essays, most of them lamenting how there is no biography on Rafi that critically analyses his oeuvre. I don’t think I can be the one looking at Rafi’s music critically either. But what I want to do is to look at the way Rafi’s voice was a part of every phase of my life.

I am, for instance, sitting at a cafe overlooking the Arabian Sea in Mumbai’s Andheri district. This cafe is one often frequented by the Hindi film industry’s young starlets, writers, and directors. I sit in front of a large glass window and watch the rush of early evening traffic pass me by, humming ‘Ae Dil Hai Mushkil Jeena Yaha, Ye Hai Bombay, Meri Jaan’, feeling the song in my bones and thinking about all the Rafi songs that come to me in the voice of my Baba.

In most of my previous works, I have credited my mother for influencing my choices. Returning to my house where I first met Rafi when he moved in, it was my Aai who was the ‘fan.’ Aai, who grew up in abject poverty, with no luxuries—no television, not even the permission to watch films in theatres or anywhere else—had only heard his songs on the humble radio. When she was allowed to watch a film for the first time, it happened to be a Dharmendra film. When Dharmendra began singing, Aai put two and two together, and it came out to be five. It was Dharmendra’s voice she was hearing on the radio, little Aai said to herself and believed it.

Just like Guddi’s illusion about the world of cinema in the Hrishikesh Mukherjee film, Aai’s illusion too soon broke. It was too perfect a story she had built in her mind. It never stood a chance. Ultimately, she gravitated towards sad songs, from ‘Tujhe Jeevan ki Dorr Se Bandh Liya Hai’ to ‘Rang Aur Noor ki Baarat.’ She taught me how to love ‘sad’ songs in Rafi’s voice. But it is my Baba who taught me how to love irreverence and joy. And that, too, was in Rafi’s voice.

This is why I want to spend the next few hundred words exploring how Rafi may have sung songs for the likes of Dharmendra and Dev Anand; his voice belonged to Shammi Kapoor for his flamboyance, Johnny Walker and Mehmood’s goofy sincerity and my Baba.

Who’s the hero?

There is a famous anecdote from the 1970s. In 1969, Shakti Samanta made an unconventional film. The budget for that was low. The story was risky. It saw a young woman becoming pregnant before marriage. It was bold enough to defend that young woman and show her struggles. And for this film, Samanta was launching a new face as the hero. Because the film was being made on a tight budget, Samanta couldn’t afford Shankar-Jaikishan for its music and had approached SD Burman. Similarly, Shailendra wasn’t available to write the lyrics of the songs and Anand Bakshi was approached.

Aradhana’s music went on to become iconic. SD, in those days, was supporting a young singer from Khandwa, making him the voice of his songs. Kishore Kumar was given two songs in the film. Roop Tera Mastana and Mere Sapno Ki Raani went on to carve their names in cinematic history. Rafi’s Gunguna Rahe Hai Bhawre paled in comparison.

It was the only album of SD’s that year, and it won him the Filmfare Award. The film made Rajesh Khanna a household name and launched an era of his superstardom. Women, it is said, slept with his picture underneath their pillows and began sending him love letters written in blood (whose blood, we don’t know). There are stories that once Khanna became India’s first superstar, he decided he didn’t want Rafi to be the voice of love for him. It had to be Kishore Kumar—the man whose voice had made Khanna an object of desire.

The ‘60s were when Rafi was at his peak, but the ‘70s witnessed a swift decline. As Kishore’s star rose, Rafi’s subsided. It would require a critical film and music analyst to put together the reasons behind this fall. I can only conjecture.

While Rafi lent his voice to a vast array of leading men throughout his illustrious career, including Shammi Kapoor, Dev Anand, Dilip Kumar, Dharmendra, Johnny Walker, Mehmood, Guru Dutt, Shashi Kapoor, Bharat Bhushan, and Amitabh Bachchan, it is his work with Shammi Kapoor, Johnny Walker, along with two specific songs for Guru Dutt and Bharat Bhushan, that particularly pique my interest.

Shammi Kapoor, Body and Soul

From Yahoo! Chahe Koi Mujhe Jungli Kahe to O Haseena Zulfon Wali, each of these Shammi songs was brought to life by Rafi. Shammi once famously said, “He was my voice, just as Mukesh was my brother’s. But my brother sang in other voices too. I couldn’t dream of any other singer. Rafi could capture my wildness, my unpredictable dance moves, in his voice. It was as if he could penetrate my body and soul”.

Raj Kapoor’s younger brother, Shammi, was stitched from a different cloth, unlike the actors of his time. He danced and twerked to Yahoo!, while others chose to brood. While working in what would be called formulaic films, he brought his Elvis Presley-esque sensuality to his songs, marking his niche within the industry that tended to take its heroes all too seriously. Shammi’s songs weren’t shy. They openly embraced his exuberance, his flamboyance, his wildness, and they didn’t shy away from sex either.

I remember discovering the song ‘Kisko Pyaar Karoon’ as a kid. The song immediately became a risque joke for the 10-year-old me, who was drawing linguistic parallels between ‘kis’ or who and kiss. They sounded the same, and Rafi sang the song, lingering longer on the ‘s’ of the kis to create that illusion. What the 10-year-old child did not interpret was the meaning of pyaar as a verb in the song. Or what the ‘Raat Ke Humsafars’ were going home to and why they were tired. There was a certain element of performance in Shammi, a breaking of conventional masculine portrayals that, through a contemporary lens, one might consider a form of "queerness." This was amplified by Rafi’s masterful singing, which seemed to embrace and even underscore this departure from the norm, subtly pushing against societal boundaries around love and its complexities on screen.

What I've termed "queerness" in Shammi's persona, Mahesh Bhatt astutely recognised as "abandon." This "abandon" set Shammi apart and, paradoxically, hindered his critical acclaim. In an era where leading men often projected stoicism and controlled emotion, Shammi's unrestrained exuberance — his swooning of women, his overt display of vulnerability ("wearing his heart on his sleeves") — positioned him as an outlier. Think of the song ‘Ehsaan Tera Hoga Mujh Par,’ from the film Junglee, where you can see him surrendering to Saira Banu.

This "abandon," this willingness to shed conventional masculine reserve, can be seen through a queer lens as a subversion of traditional norms. It embraced emotional expressiveness and a flamboyance that deviated from the dominant, often more rigid, portrayals of heroism. His lack of "serious roles," as the critics lamented, was perhaps a consequence of this very "abandon," this "queerness" that refused to conform to established notions of a leading man's gravitas.

Rafi’s voice allowed this abandon in Shammi’s work. It is impossible to imagine a Shammi song without the voice of Rafi. If Shammi could convincingly dance to songs on the stage, on boats, on a helicopter, pretty much everywhere, Rafi could make space for those movements effortlessly in his singing. However, then came the ‘70s. Khanna’s meteoric rise, followed by the rise of the ‘Angry Young Man, ’ Shammi’s career experienced a decline. And so did Rafi’s.

Johnny Mera Naam

It is often said that Cinema holds a mirror to society. The shift in the storytelling styles from the ‘60s to the ‘70s bears testimony to it. The ‘70s saw the rise of rage; it was marred by two wars, rampant poverty, unemployment, and political turmoil in the form of the Emergency declared by the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, which led to violence across the country, giving voice to rage. The hero of the ‘70s, written by arguably the best screenwriter duo the industry ever saw — Salim-Javed — imagined the Angry Young Man. It was a response to the rising injustice in the country. But a side effect of that was also the demise of the character actor. With the rise of the Hero against the system, the character actor was reduced to a mere prop, someone the hero had to save.

But in the days of optimism of a newborn country, it was possible to imagine a dignified life for everyone. While statistics mean very little in the larger scheme of things, they still help paint a picture. Kishore Kumar sang the most songs in his career for Rajesh Khanna— a total of 245 songs across 92 films, followed by 202 for Jeetendra, 131 for Amitabh Bachchan and 119 for Dev Anand. These were all songs filmed on the protagonist. While Kishore Kumar sang for the likes of I.S. Johar in the days of the Emergency, it was also for films where Johar played central roles. Compared to that, Rafi sang 145-odd songs for Johnny Walker.

This isn’t a comparison of the two singers, but it marks a change in trend in the film industry. With character actors losing significance in the films, they weren’t given songs. This makes the songs Rafi sang for Walker even more important. They were meant for voices from the margins. From ‘Sar Jo Tera Chakrae’, from Pyaasa, a song my mother would sing for me while giving me the ‘champi’, to ‘Jungle Mein Mor Naacha’, there was a Walker song for all seasons and reasons.

The voices from the margins were allowed not just to exist but to thrive within the nation’s imagination was also reflective of the Nehruvian socialism and its influence on the Indian psyche. Why the Johnny Walker-Rafi duo becomes essential in this is because he was a character actor who didn’t have the ‘look’ of a hero or even a villain. He wasn’t Pran or Shatrughan Sinha. He was a scrawny little man who would be seen serenading a woman on Marine Drive—Ye Hai Bombay, Meri Jaan—or following an angry girlfriend—Suno Suno Mr Chatterjee—or romancing his coworker—Jane Kaha Mera Jigar Gaya Ji.

You didn’t need to be a hero. You just had to be a person. This is why I begin this essay with my Baba. My Baba could never be a Dilip Kumar or a Rajesh Khanna. He is as far removed from the machismo of a hero as possible. And still, whenever I hear a Rafi song, the first voice I hear is that of my father.

A decade ago, when I bought my first smartphone, I ascribed ringtones to everyone I loved. For Baba, that ringtone was ‘Main Zindagi Ka Saath Nibhata Chala Gaya’ from the film Hum Dono. Because I grew up listening to Baba sing this song, but also because he emulated it in life. Rafi’s effortless singing adds a certain soft yet disenchanted texture to this song that talks about taking life as it comes. It is how I saw my father living his life. Rafi was the only playback singer for the songs of his life.

Caravan ki talaash

The ever-present voice of my childhood, my "housemate" Mohammed Rafi, possessed a striking breadth of emotional expression. My early exposure to film music came through the Doordarshan show Chitrahaar, broadcast every Sunday morning. One such morning, while having my Sunday poha, a staple Marathi household habit, a song came on TV. A broken, tired-looking man lamenting his sorrows in front of an unreceptive audience, which sadly included me.

The man was Guru Dutt. The song was ‘Tang Aa Chuke Hai’. Rafi carried the song on his shoulders alone. There were no instruments, no music to support him. In that melancholic masterpiece, his subdued intensity and nuanced delivery painted a vivid portrait of weariness and disillusionment. I was far too young to appreciate the nuances of Sahir’s lyrics, Guru Dutt’s performance, and Rafi’s masterful vocals. But, despite my 6-year-old self’s grievances against the song, it stayed in memory and later became a companion in some embarrassingly miserable moments.

‘Tang Aa Chuke Hai’ also stands as a powerful testament to Rafi’s vocal command, navigating high and low intensity notes, controlling his breath, and modulating the emotional arc through each couplet — a breathtaking display of his artistry.

It isn’t possible to single out Rafi songs, and it is a fruitless exercise all the same. The astonishing spectrum of his sing, ranging from devotional surrender in the name of love — Ye Ishq Ishq Hai, Ishq Ishq — to the connection of the depths of existential fatigue and despair — Tumhari Hai Tum Hi Sambhalo Ye Duniya — what connects me to Rafi is his ability to never betray the actor he is singing for and the listener. His ability to not just embody the person he voiced, but also the mood and emotional turmoil, allowing him to sing from the very depths of the character, made his voice the soundtrack of countless lives.

However, it needs to be reiterated that while Rafi remains a revered figure within the Indian music industry, having influenced singers from Mahendra Kapoor to Sonu Nigam, there has been little to no academic inquiry into his work. Perhaps a reason could be the lack of a cult of personality. Rafi remained ‘behind the scenes’, didn’t make any enemies, and always remained a humble man who just knew one thing — music. This singular commitment perhaps contributed to his somewhat outlier status within the often image-conscious world of Bollywood.

Mohammed Rafi's legacy extends far beyond the vast catalogue of songs he left behind. His voice became an era's very soundscape, shaping millions' emotions and narratives. His unparalleled vocal range and emotive depth continue to resonate with listeners across generations even today. For me, the voice that once echoed through our childhood home ended up becoming an indelible part of my personal history, often being the soundtrack of my life.

Each year, on his death anniversary, my Aai remembers him, and his songs are played that entire day in our home as a form of not mourning but remembrance and love. A good part of my childhood can be heard in his voice. A lot of my great memories would not have been without his presence in my house and my life. Rafi would have been a 100 this year. But what is a century if not an irrelevant number? What Rafi has left behind will be remembered for millennia. The notes that once danced through our home continue to linger, a testament to a voice that not only scored a nation's dreams but also intimately colored the quiet symphony of my own beginnings.

Note: I wrote this essay on Mohammed Rafi for the second edition of the Bhubaneshwar Film Festival. The photo is the cover image of the book, Moods and Madness, In Memoriam. It carries essays on Guru Dutt, Raj Khosla, Ritwik Ghatak, Tapan Sinha, Shyam Benegal, Raj Kapoor, Salil Chowdhury, and a few others.

Very nice, detailed piece about my all time favourite. He was sent to earth by the Gods for a short while to spread bliss and happiness .

I’ve written a short story woven around the legend here . Do take a look if you can

https://open.substack.com/pub/sunilsemail/p/meri-awaaz-suno-listen-to-my-voice?r=azudn&utm_medium=ios

What a beautifully woven tapestry of memory and melody! I confess I had to pause mid-read when you mentioned 'Pukarta, chala hun main' - found myself humming those lines before I could continue. There's something magical about how you've connected Rafi's voice not just to your Baba's morning serenades, but to the broader canvas of a changing India - the shift from the optimistic 60s to the turbulent 70s, the way cinema mirrored society's moods.

The mention of Chitrahaar brought such a wave of nostalgia! Your essay is a beautiful tribute - to Mohammed Rafi, to your Baba's voice carrying his spirit, and to the way music becomes the invisible thread connecting generations.

Thank you for this lovely read.